Editor's note: The following is a guest post by Bob Hoyler, a senior research analyst at Euromonitor International. Views are the author's own.

In 2020, the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States sparked much talk of an "urban exodus" in which white-collar workers – freed from being tethered to physical offices by the rise of permanent work-from-home arrangements – would flee the urban cores of the largest U.S. cities in droves for the space and relative safety of outlying suburbs and smaller cities. So far, however, the most dramatic predictions of a tsunami of urban refugees have yet to be realized.

Both New York City and San Francisco, specifically, did see significant population outflows in 2020, and suddenly booming property markets in the suburbs surrounding a handful of other large cities (such as Chicago) suggest that the populations of these cities may also be set to decrease as more households decamp for the suburbs. Yet in many other large cities – such as Los Angeles, Houston and Phoenix – populations have remained relatively stable over the course of 2020, and warnings of an urban exodus seem to have been overstated. As a result, as 2021 progresses, expect a lot of ink to be spilled about how U.S. cities are poised to bounce back over the next few years as the country attempts to recover from the darkest days of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Yet while the grimmest warnings of an urban exodus are unlikely to be fully realized, certain factors are undoubtedly working against urban population growth – and in favor of suburban population growth – in the immediate post-COVID future. One is the rise of remote work. According to Euromonitor International's "Voice of the Industry: COVID-19" survey, which was conducted in October 2020, 70% of North American-based professionals who responded to the survey indicated that they expect their businesses to expand remote working going forward.

Even if it is unlikely that most U.S. businesses will allow all staff to work from home all the time, it is a certainty that many businesses will allow employees to work from home more than they had before the onset of the pandemic. If workers commute to the office three days a week as opposed to five, they may be more inclined to live farther away from their workplace, especially if they can trade up to a larger living space in the process. This development is likely to boost suburban populations at the expense of urban cores.

It is fundamental for retailers to understand, however, that the importance of suburban consumers in the U.S. was already growing considerably even before the COVID-19 pandemic threw the country for a loop. In the immediate aftermath of the financial crisis of 2008 to 2009, one could accurately state that members of the large millennial generation were flocking to core urban areas in huge numbers, thus fuelling urbanization and the corresponding retail trends that urbanization brings.

As the millennial generation aged, however, this trend began to be overshadowed by an ever more dramatic wave of suburbanization. According to analysis of U.S. Census Bureau data conducted by William Frey of the Brookings Institution, the population of suburban areas in the U.S. has actually been growing more rapidly than that of urban cores since 2013. Because of this, overall population growth in the suburbs over the previous decade was substantially higher than the population growth of the nation's large cities.

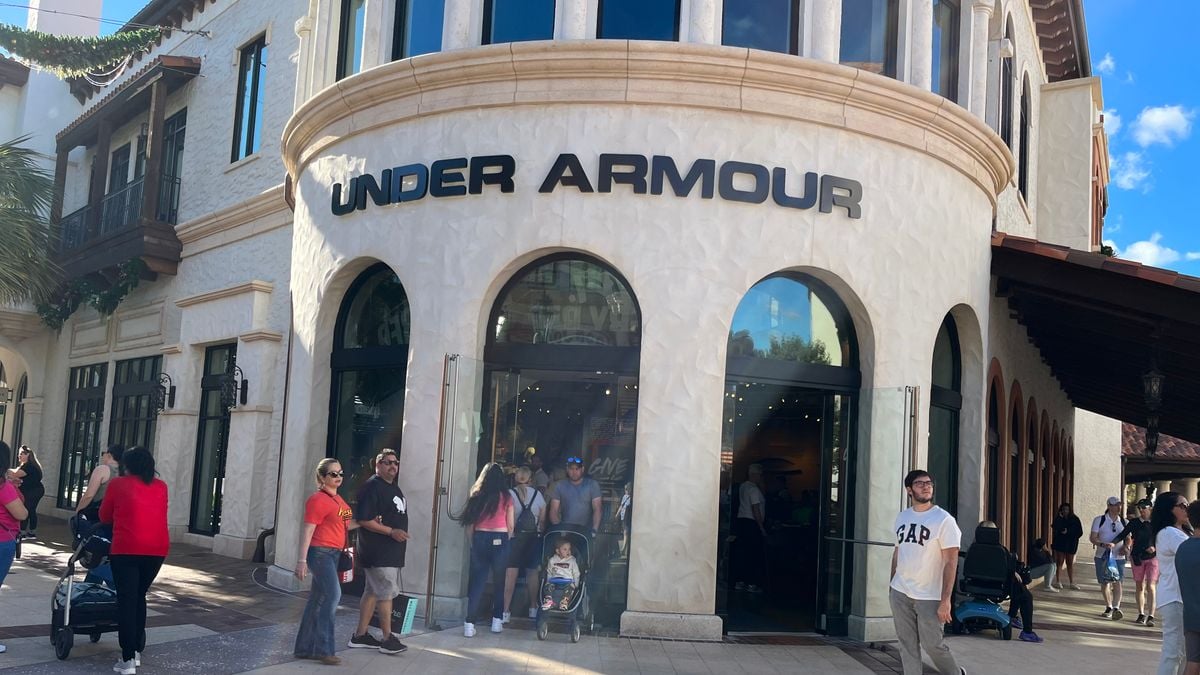

Yet even as the population growth of outlying suburban areas over the last decade outstripped the corresponding gains of large cities, many businesses in the U.S. retail sector seemed to be operating under the assumption that the exact opposite was happening. An extremely long list of retailers in the years leading up to 2020 focused most of their attention on opening showroom stores in city centers and developing other urban core-specific store formats that were designed primarily to appeal to a much-catered to demographic of relatively affluent city-dwelling millennials. Meanwhile, the hard work of making necessary improvements to suburban stores – such as building out essential omnichannel infrastructure – was often overlooked. The main streets of suburbia just did not seem to grab many U.S. retailers' attention in the same way that the high streets of big cities did.

COVID-19 has exposed the short-sightedness of this city-centric approach, and many retailers now find themselves scrambling to adjust to a suburbanization surge that was long in the making even before the pandemic. In light of this, there are a few strategies that would be wise for these retailers to adopt. Although it is exceedingly unlikely that the enclosed suburban shopping malls that were such a driving force in the U.S. retail sector in the 1980s and 1990s will ever return to their former glory, companies should take a long, hard look at other suburban retail environments when scouting potential outlet locations.

Examples of potentially attractive locations include the decidedly unsexy but remarkably resilient strip mall or its more upscale cousin the lifestyle center, especially those that are situated near residential areas or off busy commuter thoroughfares. Even more importantly, retailers should take a suburb-focused approach to building distribution centers, warehouses and other infrastructure needed to bolster the future growth of digital sales. Furthermore, they absolutely must revamp their existing suburban stores to better support these efforts by optimizing store parking lots for curbside pickup service and by devoting a greater share of the space available in their brick-and-mortar outlets specifically to the fulfilment of e-commerce orders.

It has become something of a cliche to state that the COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated pre-existing trends, but when it comes to U.S. internal migration, this statement could not be more accurate. Retailers must plan for a future in which suburban consumers constitute an expanding share of their customer base if they wish to succeed in the 21st century.