Editor's note: Mohit Mohal and Jonathan Sharp are managing directors with Alvarez and Marsal's Consumer and Retail group. They can be reached, respectively, at [email protected] and [email protected]. Views are the authors' own.

It's no secret that department stores in the U.S. are in a steady decline, with stores closing left, right and center. The critics have been vocal about the viability of this format longer term. Many even say department stores have tried everything under the sun (becoming digitally savvy, loyalty programs, curated assortment, in-store experience), but in vain. Off-price and digital have been the biggest winners at the expense of a slow and painful demise of what was once the beloved department store.

However, what is not being said enough is the unique value proposition that only department stores can offer and how they can redeem themselves back to their glory days. We should be careful not to confuse a trend with an outcome. Trends can be altered, and the history of business is littered with companies that reinvented themselves into new, viable models that combine inherent advantages of location, scale and brand with new, emerging trends. Remember when Netflix began business by renting out DVDs by mail, and Amazon as a used bookstore operating out of a garage? The challenge here is whether the leaders of department stores can make a compelling case to investors that they have a viable future play.

For a consumer, even today, the department store is one of few places to compare functionality, style, fit and other tangible features of multiple brands under one roof. When done right, a curated aisle at a department store is stronger than the now-fatigued endless aisle. This is especially relevant longer term, as Gen Zs continue to shift toward brick and mortar. By the way, have you noticed how Gen Zs love 35mm film cameras and video cams?

For them, rediscovery is the distinction that sets them apart from the millennials who came before them. They are "combiners" — they even print out photos from camera film, then photograph these on their phones and post them to Instagram. These prints have an authenticity apparently lacking from iPhone's point and shoot. This group want retro brick and mortar, and Insta-worthy experiences. Couple that with an expert salesperson who can connect with you, talk about different products, brands and make you feel like royalty. Oh, and how easy is it to grab a bite to eat, a coffee or a glass of wine with your friends while surfing Amazon from your couch?

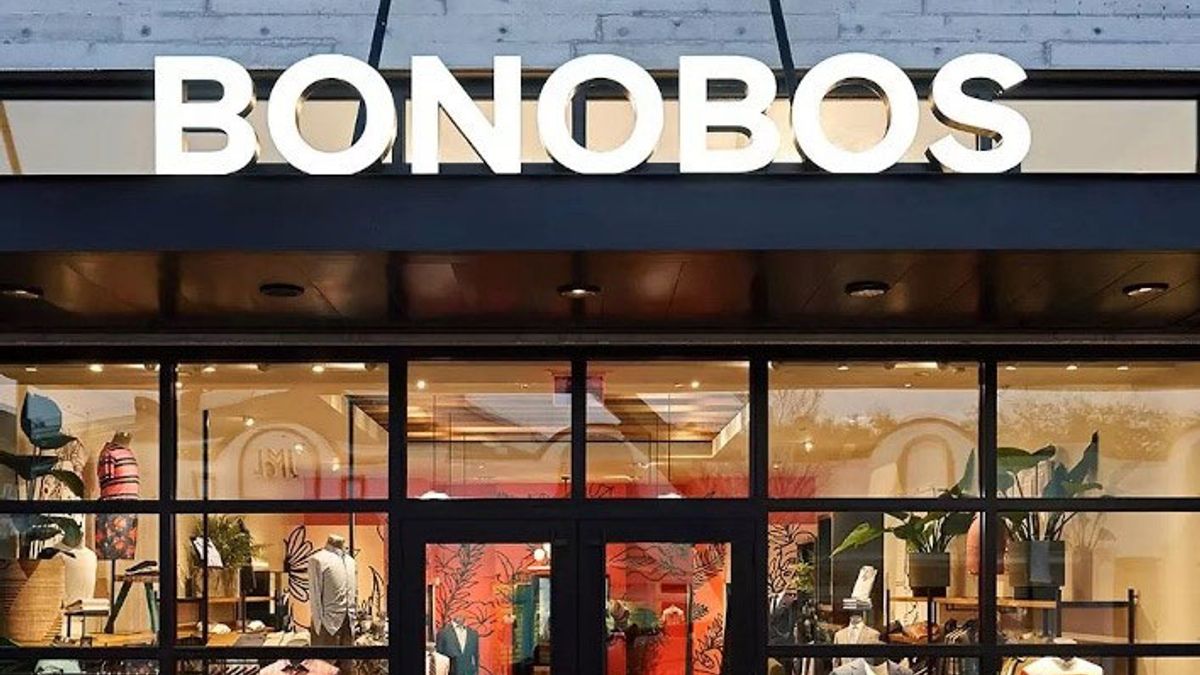

As an individual brand, no matter how many stores you open, you will never have the reach of a department store network (the top four U.S. department stores have about 2,600 doors). Furthermore, if you are an up-and-coming brand, department stores give you the chance to put a curated product assortment in the same space against competition and more established brands. None of this is possible in a small box format — and we feel department stores have a viable future. But there are key strategic questions along the way.

So what can department stores do to reinvent themselves? Simply put, U.S. department stores need to stop playing catch-up and look at success stories in geographies like the U.K., France and Japan for ideas to fundamentally reset their destiny. As an example, in Japan — given the cost of real estate and population density — department stores are probably 10 years ahead of the U.S. in their evolution. You could be working in a Tokyo office in the morning, go online and pick three dresses that interest you, pick a time slot to go visit the store, go to a trial room where the clothes are held for you, and if you like what you tried, pay and check out with your chosen dress delivered to your home. Here the department store range, physical location and touch-and-feel opportunities wield significant advantages over digital players.

A lot has been said and written about what department stores need to be focused on, ranging from being digitally savvy, omnichannel capabilities, curated assortment and in-store experience. While we believe all of these are relevant, there are three key things that matter the most.

1. Focus on their strengths and stop trying to be everything for everyone

After the last recession, premium and value retail saw a huge boom (for example, premium retail was up 80% and value retail was up more than 300% between 2010 and 2015). Coming out of the pandemic, we are going to see the same trend amplified again as a fight to value and flight to luxury. We believe there is also a possibility that Amazon will acquire a struggling national department store network in the next decade — which would further accelerate digital adoption in the value segment and squeeze department stores further, especially those focused on the middle-class consumer. U.S. department stores need to critically re-evaluate their target consumer and fundamentally reset the customer value proposition. That customer value proposition should then drive decisions around format, footprint, location quality and assortment.

Let's play an imagination game. Imagine there was a location close to you that combined the smartest range of interesting fashion, luxury brands alongside upcoming designers you cannot find anywhere else, makeup and skin care advice that was expert and trustworthy, with appointments you could arrange online beforehand. This place also offered venues to rest, eat, drink and chat. And alongside all this spending there were activities to stimulate you and your family's mind and spirit.

Join a Peloton class after shopping, leave the children in a Kumon class, get some physio or dietary advice, get the pet pampered and talk to a fiduciary about your retirement planning. Imagine this place existed. Would you be more interested in visiting it than a store with row after row of polo shirts, all 40% off? At Selfridges in London, you can sample almost any type of cuisine and top-flight wines, and you can take in a movie at their two-screen cinema. Not all department stores look the same.

2. A footprint which is at least 50% smaller, with emphasis on location quality

A bigger footprint is not better, especially given the U.S. department store density is three times that of Europe. As it comes out of bankruptcy, Neiman Marcus has talked about its intentions to tighten its footprint after it shuttered numerous unproductive doors. Most major U.S. department stores need to make a proactive and serious effort to tighten their footprint. We believe this footprint for some of the larger department chains needs to be cut by at least half, if not more of the current footprint.

With continued expansion in digital and off-price, it would be very difficult for department stores to win on value, but location quality and catchment can be big differentiators in driving traffic, especially higher spending traffic. Having a location at every major mall is sub-optimal, as malls continue to die a painful death (as an aside, the reform menu we present for department stores is not too far off from the changes malls also need to consider). The importance of location is best demonstrated by Harrod's — its historic building on Brompton Road in London's Knightsbridge being the strongest performer by sales per square foot of anywhere in the world.

3. Reset relationships with brands, especially digitally native brands, to drive traffic

As the role of the store has evolved from transaction center to hub for customer experience, established brands have questioned the strategic intent of wholesale as a channel. From a brand perspective, traditional wholesale offers relatively lower margin compared to its own stores or direct to consumer. In recent times, initiatives like drop shipping have further placed brands and department stores at cross purposes.

Establishing relationships with brands becomes increasingly important, as Amazon, Walmart.com and Target.com all try to woo brands to their own channel and focus on exclusives. A curated — even better, an exclusive — assortment that can drive significant consumer traffic should be the cornerstone of any relationship resets. Think of Selfridges in London being first to have the Apple Watch and having it exclusively in the U.K. for about a month. Or for another example, Topshop driving newness and trendiness in the store with up-and-coming brands that excited their millennial consumer base and reverberated from store to Instagram with ease.

The journey ahead is going to be hard, and tough times call for tougher measures. It is clear there will be more casualties in the department store space in coming years. The question remains, which ones will be savvy enough to reinvent themselves while their destiny is still in their own hands? We know the conditions are getting harder and we know customer expectations continue to transform. But we don't think the past is automatically predictive of the future. We should be careful that a failure of imagination does not become the failure of this retail sector … and what was once our beloved department store.